| Stomachion | |||||

|

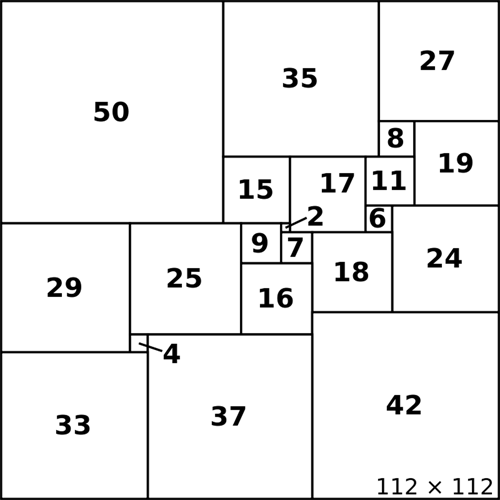

Squaring of the Square A challenging problem that engaged mathematicians for at least a hundred years is the decomposition of a rectangle or a square into differently sized squares. The general problem is to cover (or tile) a rectangle or a square seamlessly and without overlap with smaller squares, each having different side lengths and integer values. At first glance, this seems like a trivial problem, but it turned out to be very complicated. The first rectangle divided into squares was presented in 1925 by the Polish mathematician Zbigniew Morón (1904-1971). He discovered that a rectangle of 33 x 32 can be decomposed into nine squares with side lengths of 1, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, and 19. For years, mathematicians claimed that the decomposition of a square into squares was impossible. This is exactly what four students, William Thomas Tutte, R. Leonard Brooks, Arthur Harold Stone, and Cedric Smith, attempted to prove at Trinity College in 1936. They failed to prove it, but instead, in 1940, they presented the first square composed of 69 squares. Brooks later reduced the number of square tiles to 39. The side length of the composite square was 4920. It wasn't until 1962 that the Dutch computer scientist and mathematician A.W.J. Duivestijn proved, with the help of a computer, that every square tiled with squares consists of at least 21 tiles. In 1978, he discovered and proved that there is only one such square, with a side length of 112.

|

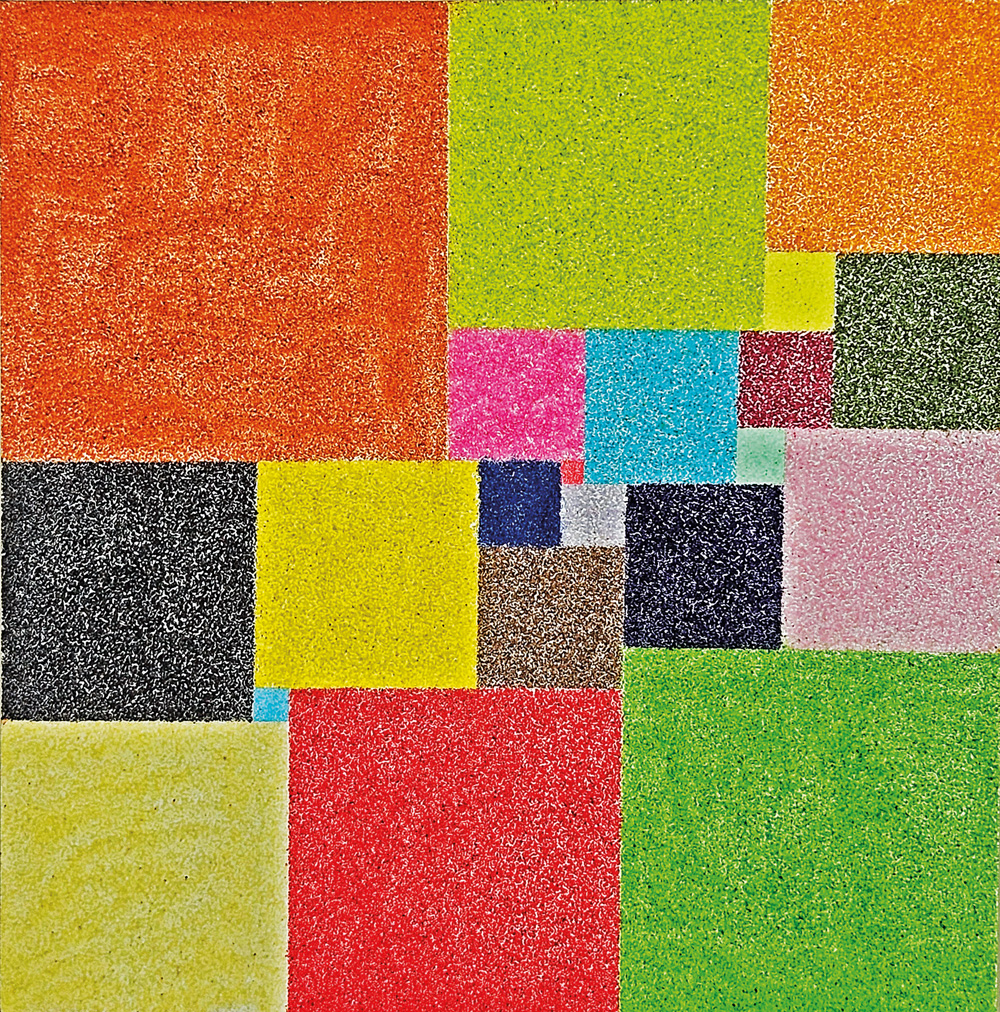

Perfect Square: Colored sand on Kappa lightweight panel (50x50 cm). Representation of the simple perfect square discovered by A.W.J. Duivestijn with the smallest possible order of 21. |

|

|